What is intelligence?*

How to compare the abilities of humans and machines

A common pleasure is to discover the light that another approach sheds on yours. Throughout this series, I will be showing how the scientists studying machines and humans can learn from each other. This week I’ll explore four principles of intelligence that those pursuing AI have prized: imitation, learning, prediction and simulation.

These principles allow us to make comparisons either way: each reveals a different aspect of human intelligence, and the parallels also make AI behaviors easier to understand. But today’s humans and machines are different in important ways that also shed light on where AI can go next.

These are not just academic debates. They can explain the puzzling current flaws of AI and show how they could be fixed. So let’s get going…

Intelligence as imitation

We can start with the idea that the appearance of intelligent behavior signals intelligence. Many people will know that Alan Turing tried to address the question of “Can machines think?” by means of “a game which we call the imitation game”. The core idea of this Turing Test is whether AI can convince a human that it is a human. (The paper actually presents the test in terms of imitating different genders, and it’s not clear how far the proposal was a serious one.)

The Turing Test is well known, and many of today’s LLMs could pass it, even though most people think they still lack artificial general intelligence (AGI). The ELIZA effect has shown for decades that humans have a tendency to anthropomorphize computers. But “intelligence as imitation” should still interest us because:

Although current attempts to define AGI go beyond the Turing Test, they agree with its crucial move to focus on capabilities (“what it can do”), rather than on processes (“how it works”).

Turing’s proposal is fundamentally a test of humans, not AI. We are the arbiters and therefore what influences us is what counts. Maybe that’s a limitation, but it shows how the human-AI link has been there from the start.

Intelligence as learning

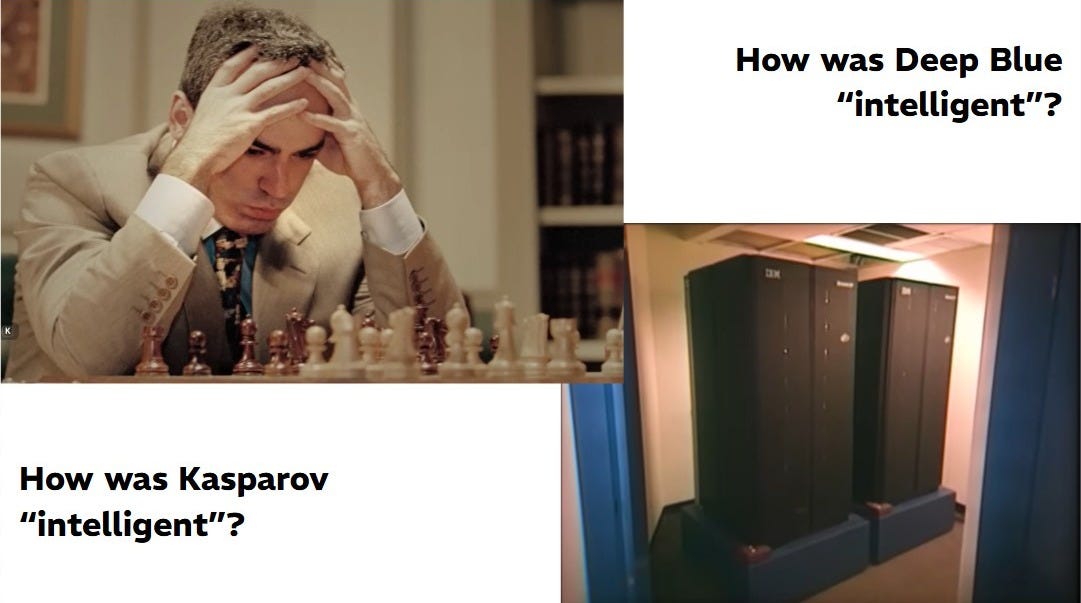

The 2024 documentary The Thinking Game is on YouTube and you should watch it. Clicking on the link will take you to the dramatic footage of Gary Kasparov resigning against IBM’s Deep Blue in 1997. The question I pose to my students is how the intelligence of the two opponents differed.

Cue Demis Hassabis:

My main memory of it was that I wasn’t that impressed with Deep Blue. I was more impressed with Kasparov’s mind. He could play chess to the level where he could compete on an equal footing with a brute of a machine - but, of course, Kasparov can do everything else that humans can do, too. It’s a huge achievement, but the truth of the matter was that Deep Blue could only play chess. What we would regard as “intelligence” was missing from that system: this idea of generality and learning.

This criticism is not new. As Turing himself noted, back in the 1840s Ada Lovelace raised a similar objection to Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine, arguably the first computer. “The Analytical Engine,” she argued, “has no pretensions to originate anything. It can do whatever we know how to order it to perform.” On the one hand, crunching through known combinations; on the other, wider application and discovery.

Fast forward 20 years: Demis Hassabis, then head of Google DeepMind, has acted on his criticism. He’s targeted the game of Go, which is seen as much more complex than chess - and therefore beyond the Deep Blue approach. Instead, the program AlphaGo trained an artificial neural network on human Go matches, but then learned by playing repeatedly against different versions of itself. During a match against Lee Sedol in 2016, it made the famous “move 37”. Sedol was so surprised that he took fifteen minutes to respond. Human observers were mystified: it was an unusual decision; it wasn’t clear what AlphaGo was doing. But eventually they realized its ability to learn had resulted in creativity.

Later versions of the program gradually dispensed with the human scaffolding: the program was deprived of starter games (just the rules), and later had to discover the rules itself. Its ability to learn meant it kept winning. This trajectory illustrates what has been called the “bitter lesson” of AI development: approaches that rely on human input or expertise (telling a program how to play chess) end up getting dominated by those that exploit increases in computational power.

Intelligence as prediction

Critics of LLMs will often say that they are “simply predicting the next word.” In that context, it is interesting to read what many people claim the brain does. First, take neuroscientist Lisa Feldman Barrett’s account:

Trapped within the skull, with only past experiences as a guide, your brain makes predictions.

Prediction means that the neurons over here, in this part of your brain, tweak the neurons over there... Your brain combines bits and pieces of your past and estimates how likely each bit applies in your current situation.

Right now, with each word that you read, your brain is predicting what the next word will be, based on probabilities from your lifetime of reading experience.

Predictions not only anticipate sensory from outside the skull but explain it.

The brain is structured as billions of prediction loops creating intrinsic brain activity.

Then try Nick Chater claiming that The Mind is Flat:

Our brain is an improviser, and it bases its current improvisations on previous improvisations: it creates new momentary thoughts and experiences by drawing not on a hidden inner world of knowledge, beliefs and motives, but on memory traces of previous momentary thoughts and experiences.

I read this hard on the heels of this passage from The Emergent Mind:

When you ask an LLM to tell a story, it is not pulling out a story from some database. Rather, it is generating one on the fly, apparently “deciding” to produce a coherent story of a particular type simply by generating words based on previous words in its context.

We’re not just talking about words. Chater’s book, and last year’s A Trick of The Mind, show that human vision rests on prediction as well. The eye is only capable of achieving crisp color vision for a small circle at the center of visual field. The rest of that field is a colorless blur. Everything in the periphery, the whole sense of “being in a room” is a reconstruction - or rather a prediction of what the brain thinks should be there.

To get a sense of what I’m talking about, look at the image below, a grid illusion that disrupts our predictions.

Generative AI makes similar “visual” predictions. A Masked Autoencoder (MAE) is trained by hiding parts of an image, which the neural network is forced to reconstruct. In other words, learning happens by forcing the AI to predict what “should” be there, much like our brains do for our visual periphery.

Of course, the type and accuracy of predictions matter; I will point out the differences in second. But it’s hard not to feel a little surge of recognition here. Christopher Summerfield drives the point home:

It is not correct that LLMs cannot be ‘truly’ reasoning because they are ‘just’ making predictions. In fact, when it comes to learning, “just predicting” is pretty much exactly what happens in naturally intelligent systems.

In the brain, these predictions are created by forming synaptic connections, as shown in this simple interactive diagram. Famously, repeated exposure to a bell with food will ensure that the neuron that fires when a dog hears a bell also “predicts” that the stimulus (food) that causes salivation will also appear.

Of course, our thoughts are not one-to-one connections but rather “patterns of activation over collections of neurons”. The “false memory” exercise brings this idea to life. People are shown a list of fifteen words associated with a concept: for “river”, you might get “water”, “stream”, “lake”, “flow”, “bridge”, and so on - but not “river” itself. They are then asked to write down as many words as they can remember. Reliably, around half of people falsely remember that the central concept word was on the list. Their “patterns of activation” have “predicted” that the unifying concept was there.

These prediction networks directly inspired the creation of artificial neural networks. It’s not surprising, therefore, that you can (still) find evidence of “fast” associative pattern matching in even the latest models, as I showed in my previous post. What is more surprising is how some critics of generative AI uncritically hold humans up as the standard to achieve. Humans are also predictive pattern matchers - and LLMs get things wrong just like we do. Although we can take that comparison too far…

Differences between human and artificial intelligence

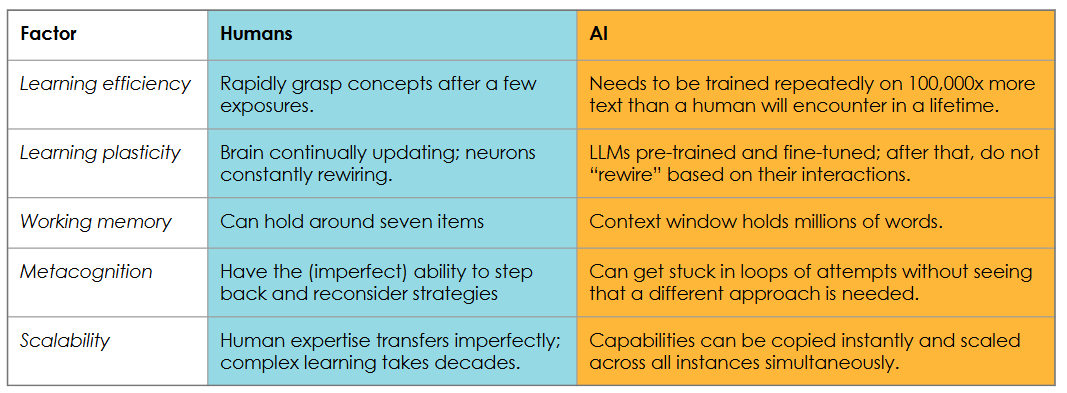

To start with, we can set out key differences in how the two intelligences learn:

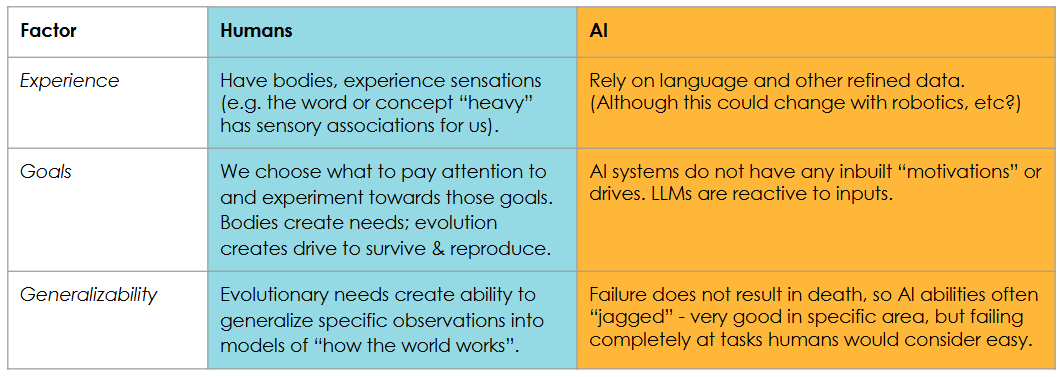

The bigger divide is revealed when we think about the “inputs and outputs” of the two intelligences. What do they work with and to what ends? Humans take in sensations from their bodies, while AI relies on language or data that is effectively experience refined. In the words of an excellent recent article in the New Yorker, you could argue that an AI’s experience is “so impoverished that it can’t really be called “experience”… Maybe truly understanding the world requires participating in it.”

And what does AI wish to do with its “impoverished” inputs? Human bodies create needs that we have to fulfil or we die; we’re driven to survive so we can reproduce. Current AI does not have needs - it reacts to ours. While AI has optimization objectives, it does not have goals like we do. Andrei Karpathy argues that this absence can explain why AI expertise is “jagged”: humans can’t just be good at a few narrow things (e.g. can only use our arms to dig a hole), since a predator could exploit this failing (compared to, say, if we could also use our arms to climb a tree).

AI does not receive the punishments for not being able to generalize that we would. But why can’t it generalize? That leads to the final principle of intelligence I’ll consider.

Intelligence as simulation

I’ll keep this short. A common criticism of generative AI is that it lacks “world models”: reliable maps of reality that allow it to plan out how things will happen (e.g. water will leak out of a cracked mug), instead of making errors that seem obvious to humans. So how did humans develop these world models?

In his book A Brief History of Intelligence, Max Bennett identifies simulation as a key breakthrough we made. Simulation is the ability of a brain to model (or “imagine”) the world internally to predict the outcomes of actions without actually performing them. You can see this as the transition from “learning by doing” to “learning by thinking.”

The critique is that generative AI cannot do simulation reliably. Instead, it relies on the traces of our simulations found in language. As Bennett puts it:

“The human brain contains both a language prediction system and an inner simulation… Language is the window to our inner simulation.”

The idea is that generative AI is currently looking through this window but cannot get inside. In the next post, I’ll talk about how behavioral science can help develop strategies for breaking in.

*(This post shares its title with an excellent recent book by Blaise Aguera y Arcas)